New Housing Need Methodology: How Many is Too Many?

At the end of 2020, the Government reviewed the standard methodology for housing delivery and confirmed their approach to future housing numbers across the country. The latest figures have backtracked from the draft proposals published as part of the Planning for the Future White Paper in August 2020, which proved controversial due to the disproportionately high numbers being allocated to the South East and London.

The numbers have now been ‘rebalanced’ to focus on the urban areas across the country. An uplift of 35% has been added to the numbers for Greater London as well as 19 of the other most populated cities and urban centres in England, including Bristol, Southampton, Birmingham, Brighton and Hove and Reading.

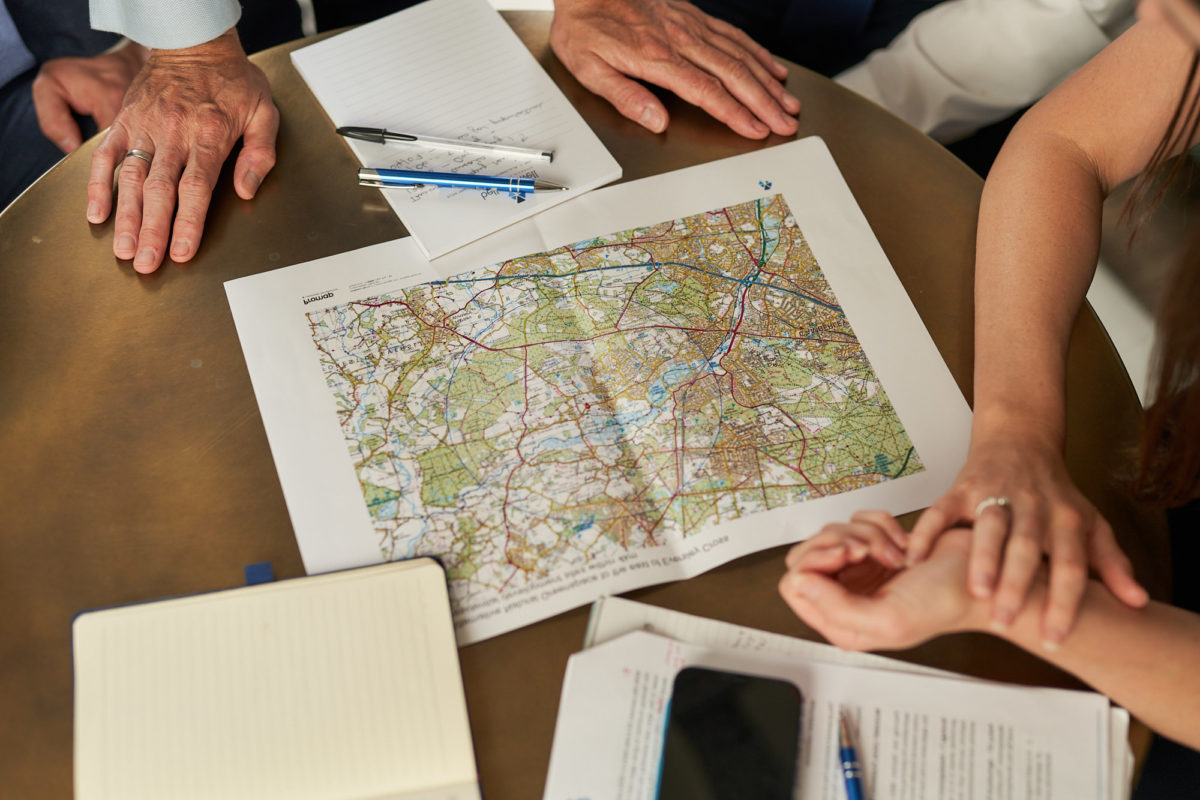

Many of these new figures have come out much higher than the corresponding Local Plan requirements currently indicate. The Government expects the homes to be delivered within the cities and towns themselves, rather than by surrounding areas, but it is unclear whether this is at all realistic or deliverable. While the shire areas may feel they are off the hook, the reality is that they are likely to be called upon to help out their neighbours.

For example, Reading is highly constrained and has an extremely limited supply of available sites meaning that in recent times it has largely delivered high rise flatted developments and not enough family housing. Its requirement will increase from around 710 dwellings per annum (dpa) to 876 using the new standard method. It is hard to see how achieving this increase is going to be possible and it’s likely that Reading will need to continue to ask its neighbours such as West Berks, Wokingham and South Oxfordshire, for assistance with the provision of family homes.

Other urban areas have far higher increases and are even more constrained – for example, Brighton, with an increase of 461 dpa to 1,247, is wedged between the South Downs and the sea, meaning that there simply isn’t the land available. This will put pressure on other neighbouring local authorities such as Horsham and Mid Sussex to help out.

The overspill is likely to be extremely unpopular amongst these neighbouring local authorities. Furthermore, the necessary negotiations involved means that the Government’s proposal is unlikely to speed up the supply or delivery of housing (read more in our article ‘Home Delivery‘) .

Whilst it may appear that there are many potential barriers to Councils achieving their new targets, the penalties for under delivery of housing must not be forgotten. We are, therefore, optimistic that the incentives to achieving the new targets will ultimately see positive results for housing delivery.